THE KNACK — AND HOW TO GET IT

A Cultural and Fashionable Prelude to Mod

Chapter One — A Nation in Recovery

Think of Britain in the late 1940s and early 1950s and the instinct is to picture ration coupons, bombed-out terraces, and a stoic nation determined to “carry on.” Less obvious, yet every bit as real, was the quiet emotional fallout. Yes, the Allies had won the war, but victory didn’t magically restore direction or purpose. The country’s adults had endured trauma, responsibility and, in many cases, loss. Their first instinct was to lock the world back into place using the tools they knew best: discipline, tradition, and the moral landscapes of pre-war Britain.

Young people, however, saw only fences.

The returning peace brought new questions no one could easily answer. What did the future look like? Who got to define it? And why should a generation who’d grown up under air-raid sirens settle obediently back into their parents’ rhythms?

What emerged was not a political manifesto but a murmur, an itch beneath the surface of post-war conformity. A belief that identity could be built rather than inherited. That style, music, and ideas could be more than decoration, they could be rebellion. The first sparks of what would become Mod would flicker here, though the flame had another name at first.

Chapter Two — The Teddy Boy Inheritance

Before Mod strutted down Carnaby Street, the Teddy Boy swaggered across it.

Teddy Boys seen here at the Thirteen Canteen, Elephant and Castle, London, 1955.Daily Mirror/Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images

The Teddy Boy, the first major British youth subculture, stepped into view in the early 1950s, wearing Edwardian-inspired drape jackets, velvet collars, bolo ties, brothel creepers, quiffs, and a stun-gun self-confidence that shocked the older generation. By September 1953, when the Daily Express printed the term Teddy Boy, the movement already felt inevitable.

Part of the punch came from across the Atlantic. American rock ’n’ roll hit Britain like a live wire. Elvis swung his hips, Bill Haley sneered his way through Billboards, and Blackboard Jungle flickered in cinema darkness with a message parents quickly recognised: this wasn’t their world anymore.

But Teds weren’t simply costumes attached to record players, they were a creative act. Boys tailored themselves into exaggerated, cartoon-sharp silhouettes; long wool drape coats for warmth on street corners (and pockets deep enough for flick knives or contraband), narrow black trousers cropped to show off brightly coloured socks, and towering quiffs sculpted with care. The look was both declaration and armour.

Teddy Girls, too often forgotten, were just as radical. Toreador trousers, circle skirts, low-cut tops, American-influenced blouses: a wardrobe explicitly designed to scandalise the older world while laying claim to one of their own.

For a moment, Teds ruled the streets. But subcultures age fast. By the end of the 1950s, the style felt loud, set, even predictable. Younger teens, never keen on inheriting their older siblings’ cast-offs, started searching for something sleeker, sharper, more modern.

And a new word began to hover in London’s night air; modernist.

Chapter Three — “I Had a Dream… and That Dream Was Mod”

The 1960s, now immortalised in pop culture as a decade of upheaval, optimism and colour, didn’t spring fully formed from nowhere. It took shape through young people who sensed the post-war dust settling and realised they now had choices.

Modernist was the word first used, not Mod, and it originally applied to fans of modern jazz. These were young listeners who rejected the trad (traditional) jazz beloved by older hepcats and instead leaned toward Miles Davis, Art Blakey, and the European cool jazz imports filtering into London. The distinction mattered. It meant sophistication over swagger. Precision over posturing. Clean lines, clean sound, clean living, “under difficult circumstances,” as Mod chronicler Peter Meaden later quipped.

The curious thing is that Mods never wanted to be easily defined. The boundaries shifted constantly and that was the point. Mod wasn’t an outfit you wore; it was a state of intent. How you dressed, what you listened to, where you spent your nights and how you carried yourself were woven from the same thread: intelligence, awareness, and the thrill of the next new thing.

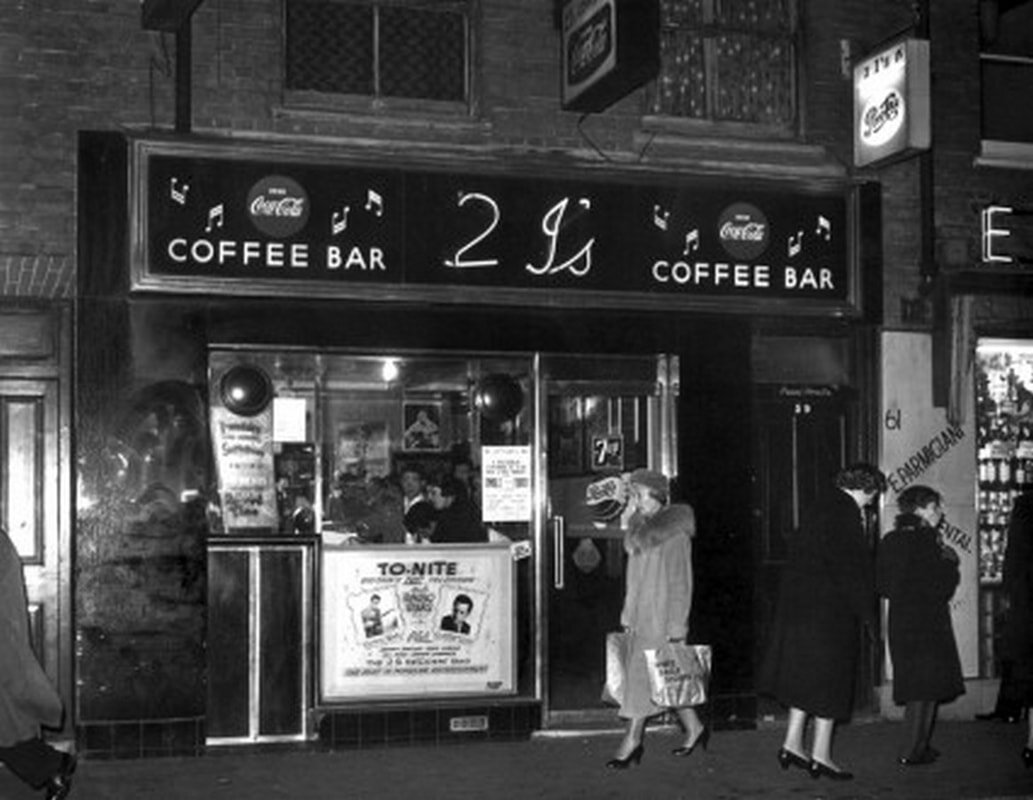

Chapter Four — Coffee Bars, Beatniks, and the Modern Mind

The 2i Coffee Bar 59 Old Compton Street, Soho, London. The 2 I's was so-called because its original owners were brothers Freddy & Sammy Irani.

To understand Mod's environment, forget pubs and imagine instead London’s coffee bars: smoky, dim, caffeinated caves where jukeboxes thumped till dawn. These were not genteel tearooms. They were meeting grounds where class distinctions dissolved, where school leavers rubbed shoulders with art students and early drop-outs from nine-to-five respectability.

The soundtrack evolved with the decade. Late-50s bars leaned on jazz and blues; by the early 60s, raw American R&B from labels like Chess and Stax began to take over. The basslines got dirtier. The dancing got better.

Lurking beneath the surface was the influence of the Beat Generation. Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and their circle weren’t simply writers to be read, they were models of how to inhabit the world. Beat philosophy taught that meaning wasn’t bestowed by institutions, it was found through self-invention. That attitude seeped into British youth culture like dye.

Young modernists educated themselves by choice rather than obligation, watching Italian cinema, poring over French fashion magazines, reading Sartre and Camus, and prowling record shops for jazz imports. Knowledge wasn’t a luxury, it was a tool of distinction.

Chapter Five — Dressing the Part

Clothes came next, not as decoration, but as precision instruments.

Early Mods borrowed ruthlessly from two predecessors:

-

From Teddy Boys; pride in presentation and the understanding that tailoring could be a weapon.

-

From Beatniks; minimalism, black rollnecks, stovepipe jeans, and a cultivated air of effortless intellectual cool.

Italian fashion quickly became the lodestar. Slim-cut suits, narrow lapels, pointed-collar shirts, winklepicker shoes, and neat, close-cropped hair created a silhouette that felt European, modern, urban.

And unlike Teddy flamboyance, early Mod style prized discipline. A faint crease in the wrong direction could ruin a mood. Shoes had to shine. Shirts had to be crisp. Identity required upkeep.

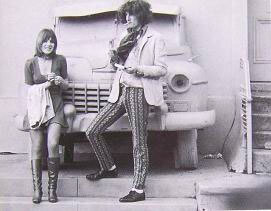

Mod teenagers in 1965 Credit: Photo: Rex

Transport also became part of the look. Lambrettas and Vespas glided into the scene; sleek, aerodynamic alternatives to the greasy rock ’n’ roll motorbike. But scooters introduced a practical problem: how to keep that immaculate suit immaculate? Enter the surplus military parka: oversized, utilitarian, and instantly iconic.

Chapter Six — Boutiques, Media Heat and the Mod Boom

By the early 1960s, the ingredients were in place; disposable income, cultural curiosity, fashion literacy, and a growing sense of collective style. The newspapers could hardly resist. Once the press named the movement, the word Mod went national.

Bazaar, the first shop opened by Mary Quant in Kings Road, Chelsea,

Youth boutiques exploded, run not by cynical corporations but by twenty-somethings who were Mods themselves. Mary Quant’s hemlines, John Stephen’s Carnaby Street suits, Biba’s dreamy cuts, these designers didn’t dictate style; they listened to it, sharpened it, and put it on rails for anyone with a Saturday job and ambition.

The High Street shifted on its axis. Clothing became a personal statement rather than a parental purchase. Youth culture wasn’t secondary culture any more—it was the engine.

Chapter Seven — Swinging London and Fragmentation

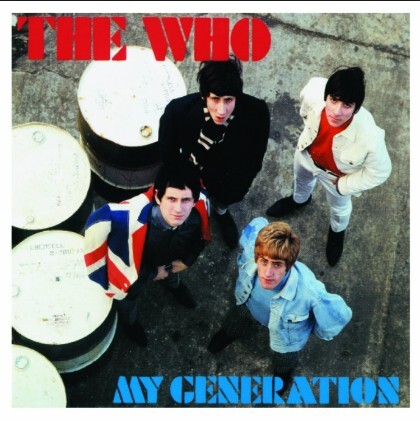

By the mid-60s, Mod had reached critical mass and burst beyond fashion into mainstream culture. Bands didn’t just dress Mod, they were Mods. The Who, Small Faces, and later The Creation and The Action amplified the look and attitude with R&B power chords and operatic ambition.

My Generation, the debut studio album studio album by the Who, released on 3 December 1965 on Brunswick Records.

Carnaby Street glittered. Pop art exploded. Nightclubs multiplied. And London—almost accidentally—became the world’s capital of the cool.

But success carries risk. By 1966, psychedelia, dandyism, and commercial appropriation began to blur Mod’s edges. Academic Dick Hebdige later argued that once manufacturers started pre-packaging “Mod style,” the underground spirit evaporated. Yet even in its mainstream moment, the DNA remained: self-creation, sharp presentation, music as identity.

And when Mod as a unified movement dissolved, it didn’t die. It simply recombined—into Northern Soul dancers, scooter clubs, freakbeat bands, skinheads, soulboys, Britpop devotees, and every generation since that’s chosen to dress sharply and move forward with purpose.

Chapter Eight — Why Mod Still Matters

So what was Mod, really?

Not just suits or scooters. Not jazz clubs or R&B. Not even London.

Mod was and is a belief:

-

that youth doesn’t have to wait to be invited into culture;

-

that style can be resistance;

-

that curiosity is power;

-

and that identity is something you build, stitch by stitch, record by record.

Its legacy is everywhere; in men’s tailoring, in street fashion, in retail design, in club culture, in the idea that teenagers deserve their own voices, and in the enduring truth that looking the part can help you become the part.

Because in the end, Mod was never solely about fashion.

It was about the knack; the mysterious, magnetic understanding that how you carry yourself can rewrite the world around you.

And for a brief, brilliant moment in British history, that knack didn’t just belong to a lucky few.

It belonged to a movement.

Inside the 1960s Boutiques…

Step through the glass door of a London boutique in the early 1960s and you enter more than a shop; you cross a cultural border. There’s a smell of fresh paint and perfume, maybe incense. Jazz or R&B pulses from a tinny record player, and racks of colour, vivid colour, cascade like a rebuke to the grey austerity Britain thought it couldn’t shake.

Welcome to the birthplace of a revolution stitched in wool, silk and PVC.

These weren’t shops in the traditional sense. Traditional retail sold clothes to people. Boutiques, on the other hand, dressed people in identity. They were run by innovators barely older than their customers, Mary Quant snipping hems on King’s Road, John Stephen turning Carnaby Street into a men’s fashion runway, and Barbara Hulanicki conjuring Biba’s dreamy, velvet-lit fantasy world. Their boutiques weren’t just places to buy clothes; they were clubs without doormen, salons without lectures, sanctuaries where youth culture set its own agenda.

Inside these narrow spaces, some impractically tiny, others glorified market booths, the Mod movement found its wardrobe and its confidence. Gone were the days of waiting for fashion to trickle down from Paris or Savile Row. If your taste ran ahead of the pack, these boutiques chased you and sometimes helped you outrun everyone else.

Designers drafted patterns at kitchen tables, experimented with fabrics that made the establishment wince, and priced garments so anyone with a barmaid’s wages or a Saturday job could walk out a walking manifesto. And every rail carried a secret; fashion was no longer something bestowed from above—it was now shaped from below.

Our upcoming pieces will take you inside the boutiques that defined the decade. We’ll step into John Stephen’s Carnaby Street empire, ground zero for Mod menswear, wander through Quant’s miniskirt revolution, descend into Biba’s gothic glamour, and explore lesser-known spaces where style pioneers cut cloth long before fashion weeks made headlines.

But first, stand here for a moment and look around. The clothes are loud, the mirrors are unforgiving, and the energy is electric. This is where the 1960s stopped being black and white.

This is where Britain learned to dress itself young.

BIBA: From Mail-Order Miracle to Mega-Store Mayhem

If the Mod movement was a spark, then Barbara Hulanicki was one of the brightest flames it produced.

Her boutique didn’t just sell clothes, it wired a generation into the idea that style, glamour and self-expression belonged to everyone, not just those with the right postcode or the right parents.

Welcome to the story of BIBA, a phenomenon that went from kitchen-table postal orders to a seven-storey style empire and burned brilliantly before it finally burnt out.

A Dress, a Newspaper Ad, and Seventeen Thousand Orders

Barbara Hulanicki’s path to retail superstardom is the kind fashion students dream about.

Art college? ✔️

Freelance illustrator? ✔️

Mail-order visionary? ✔️

Boutique queen? Oh yes.

Her first big idea wasn’t a shop at all, but a postal boutique, selling affordable pieces fans saw on style icons such as Brigitte Bardot. If celebrities wore it, Biba wanted the rest of us to wear it too.

The breakthrough came courtesy of a gingham dress advertised in the Daily Mail in May 1964.

Hulanicki and her business partner (and husband) Stephen Fitz-Simon hoped for a few hundred takers.

Instead, they sold four thousand in a day and ultimately seventeen thousand in total.

Momentum was unstoppable.

Four months later, BIBA opened its first bricks-and-mortar boutique in Kensington and British fashion would never be the same again.

Walking Into BIBA Was Like Walking Into a Film

The first store didn’t feel like a shop.

It felt like a set, a stage, a fever dream stitched together from art deco, Edwardian furniture and a dash of Mod glamour.

Dark walls.

Victorian hat stands dripping with dresses.

Antique bowls filled with bangles and lipstick.

And always, the throb of the latest sounds ; jazz, R&B, whatever swung hardest that week.

It was a hangout, a catwalk, a clubhouse, and crucially, a place where teenage girls could play dress-up without spending a month’s wages.

BIBA’s customers, many of them under 25, swamped the shop in a frenzy of colour and possibility.

The pieces were stylish yet cheap: for around 10% of an average weekly wage you could leave looking like a star.

And the stars noticed.

Models, musicians and scene-makers snapped up the clothes too, proving BIBA wasn’t just for aspirants; it was for icons in the making.

Fast Fashion Before the Term Existed

Seen Cathy McGowan on Ready Steady Go!?

By Monday morning, BIBA were selling something uncannily similar.

This was fast fashion decades before Zara and H&M.

Youth culture moved fast yet BIBA moved faster.

Word of mouth did the rest.

There were no billboards, no influencers, no multi-million pound campaigns, just giddy teenagers telling each other: You have to see this place.

And half the time, the assistants helping them at the fitting room mirrors were just as smitten, many came straight to work from the BIBA racks themselves.

Bigger Dreams, Bigger Stores

Success demands space, and BIBA soon outgrew its first home.

In 1966 came BIBA Mark II, on Kensington Church Street, the same attitude, but more of… everything.

More rails, more customers, more chaos.

Stories from the era are mythic, including Hulanicki’s own account of discovering a shipment of skirts that had shrunk to TEN INCHES thanks to fickle jersey fabric.

She panicked.

Customers didn’t.

The micro-minis flew out in minutes.

BIBA was no longer a boutique; it was a movement with its own gravitational pull.

And gravity was about to drag it somewhere bigger still.

The Rise of Big BIBA — A Fantasy With a Door

By the early 70s, Hulanicki and Fitz-Simon dared something no independent retailer had pulled off before:

turning a boutique into an entire department store.

They took over the former Derry & Toms building on Kensington High Street, seven floors, 80,000 square feet, and spent more than £1 million transforming it into a psychedelic, deco-flavoured wonderland.

Every floor had a theme.

Menswear, children’s wear, homeware, food.

Even a bookshop.

There were roof gardens, flamingos, and the famed Rainbow Room restaurant where a customer could eat, pose, and get swept into the dream.

This wasn’t shopping; it was lifestyle immersion before anyone coined the phrase.

No window displays tempted you from the street.

BIBA trusted curiosity.

The world outside was grey.

Inside, everything came in velvet, satin or lacquered shine.

Too Big, Too Bold, Too Soon

But dreams are expensive, and timing can be cruel.

Big BIBA opened in 1973, smack in the middle of a recession.

Footfall was enormous, but footfall doesn’t pay rent, purchases do.

Many came to wander the fantasy, not necessarily to buy from it.

Ownership shifts didn’t help.

Dorothy Perkins had acquired a controlling stake in 1969, offering funding in exchange for equity.

Then British Land purchased Dorothy Perkins in 1973, inheriting BIBA just as the economic floor fell away.

Hulanicki found herself wrestling with bureaucracy, competing visions, and financial caution.

She ultimately left before Big BIBA collapsed entirely.

By 1975, the grand emporium closed its doors.

The BIBA brand was sold on in 1977, without Hulanicki attached.

Her verdict, years later, was blunt:

“Every time I went into the shop, I was afraid it would be for the last time.”

She was right.

Legacy: Glitter That Never Faded

Big BIBA’s collapse wasn’t failure so much as overreach, a bold experiment too ambitious for the economic climate surrounding it.

Yet its legacy is immense.

BIBA:

-

democratized fashion,

-

invented a version of fast retail,

-

reimagined what a shop could feel like,

-

shaped the Mod and Swinging London aesthetic,

-

and left a mark on every high street chain that followed.

The clothes may have flown from rails half a century ago, but the BIBA cosmetics range remains a money-spinner, and the name still conjures velvet-dark glamour and art deco romance in an instant.

Barbara Hulanicki proved that the right dress, in the right moment, can change a business and an era.

And all of it began with a mail-order frock and a girl who saw style not as privilege, but as invitation.

In keeping with the BIBA Boutique and Emporium philosophy of good quality, affordable attire, Atom Retro has put together a little collection of Mod and Retro Clothing with a cool Vintage Sixties appeal.

John Stephen: The Man Who Made Carnaby Street Swing

This was the place to be and he was the man who made it happen.

Before Twiggy posed for Vogue and before Carnaby Street became a postcard cliché, one designer was quietly sketching out a revolution on the back of a bolt of cloth. His name was John Stephen, and if Mary Quant and Barbara Hulanicki defined the female wardrobe of the 1960s, Stephen was the man who dressed the boys.

Today, he’s finally reclaiming his place as one of Britain’s great fashion disruptors; a pioneering businessman, flamboyant designer and the undisputed King of Carnaby Street.

From Glasgow Lad to Fashion Firestarter

Born in Glasgow and London-bound at 18 in 1952, Stephen started where many future greats begin, learning the rules before breaking them. At Moss Bros, tucked inside the Military Department, he polished his tailoring craft the traditional way. But the real spark came when he moved to Vince Man Shop on Newburgh Street; one of the first menswear stores to hint that fashion could be fast, fun, and fiercely modern.

Stephen could see something no one else dared name yet, young men didn’t want to dress like their dads anymore. They wanted style, shape, colour, identity.

To fund his vision, he pulled double shifts, tailoring by day, waiting tables by night, until he saved enough to open his first shop. It was small, short-lived (a fire saw to that), but fate nudged him in the right direction regardless: toward a dingy backstreet called Carnaby Street.

His Clothes, His Rules — and the Birth of a Scene

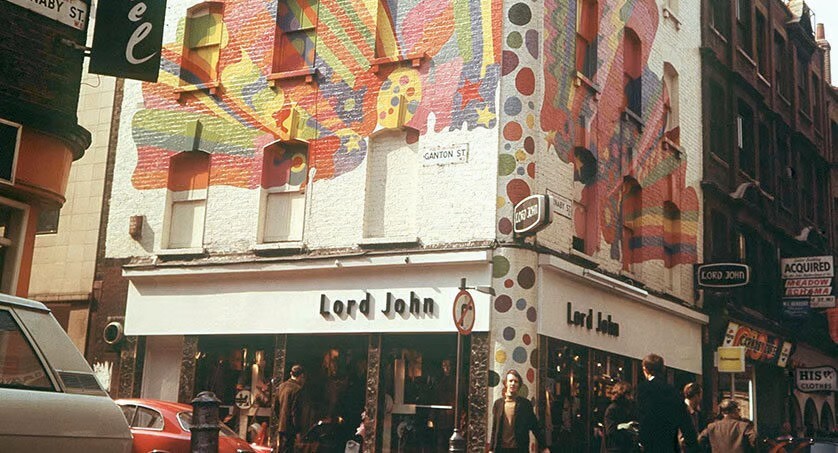

The year 1958, the setting Carnaby Street, a drab back Street in London's Soho district was nothing glamorous. But Stephen had a brush, paint, and a plan.

He slapped a coat of retina-searing yellow on his new shopfront, blasted the latest 45s, and filled the rails with jackets, shirts and trousers cut slim, sharp and modern, produced in tiny runs to keep the looks fresh. Blink and you missed them. Wait a week and something new had replaced them. Fast fashion had arrived.

Within a few years, “His Clothes” became Carnaby Street’s anchor, the wardrobe of every sharp Mod worth his Lambretta. By 1964 Stephen owned a cluster of boutiques with names as slick as his customers:

Mod Male, Domino Male, Male West One, and more.

The street exploded. From backwater to bustling Mod mecca, Carnaby Street’s transformation is virtually inseparable from Stephen’s rise and soon he controlled 15 shops there alone.

Where the girls rushed to Biba, the boys marched straight to Carnaby.

Cutting the Mod Silhouette

Even before the Beatles went collarless, Stephen was experimenting with the look, tweaking suits, cropping jackets, sharpening lapels, and adding the details Mods craved.

Among his innovations:

-

Triple- and double-button plackets on shirts

-

Paisley and psychedelic patterns before they went mainstream

-

Collarless suits ahead of the curve

-

Dandy Regency tailoring at pocket-money prices

Mod icons recognised a kindred spirit.

The Who, The Small Faces, The Kinks, all shopped Stephen’s racks.

And he always priced to thrill: a passer-by could check their change and discover they could afford that velvet jacket in the window. Democratized cool — Stephen’s secret weapon.

Her Clothes Too — The Style Story Grows

By 1967, Stephen had another intuition: the girls wanted in.

With boutiques like His N Hers and Tre Camp, he introduced womenswear dipped in the same cauldron of boldness — Mod minis, kaftans, wild prints and psychedelic palettes. His boutiques evolved into playgrounds for fashion-curious couples.

Hollywood noticed too.

Elizabeth Taylor and Marlene Dietrich reportedly added Stephen pieces to their wardrobes, proof the look travelled far beyond Soho pavements.

Changing Times, Changing Tactics

As the 1960s wound down, the Mod scene loosened its tie and Carnaby Street’s shine dulled. The imitators had arrived.

By the early 1970s the independent stores Stephen inspired had become chain-store copycats.

Never one to drift, Stephen adapted.

He:

-

Sponsored ads at the Mexico 1970 World Cup

-

Set up franchises in Russia and the USA

-

Built a Glasgow factory employing over 100 people

-

Expanded into wholesale, supplying the very high streets that once watched him warily

But the tide had turned. In 1975 the boutiques closed, and the Stephen name disappeared from the shopfronts.

Reinvention and Recognition

Stephen didn’t leave fashion. He simply switched lanes, resurfacing as Francisco-M, leaning into sharp continental styling inspired by France and Italy.

Meanwhile, history caught up with him.

In 1975, the V&A Museum acquired his full archive, now a treasure trove of 1960s design.

A commemorative blue plaque stands proudly on Carnaby Street, marking the boy who made it swing.

Legacy of a Mod Visionary

John Stephen didn’t just dress a generation, he unlocked it.

He gave young men permission to experiment, dress flamboyantly, and step into the spotlight normally reserved for women’s fashion. His boutiques created an atmosphere, colour, charisma, chaos, that helped transform a shabby street into a global symbol of London’s 60s swagger.

With Stephen came:

-

Fast fashion before the phrase existed

-

The Peacock Revolution

-

The democratisation of style

-

And the first blueprint for every menswear-led high street chain that followed

Carnaby Street may now be a tourist destination, but its legend was stitched together by one Glaswegian visionary armed with talent, instinct, and a paint tin.

John Stephen didn’t just keep pace with the Swinging Sixties; he dressed it, tailored it, and set it strutting down the street.

The Carnaby Collector.

As an intersting sign off, Atom Retro has picked out a few Carnaby Street and Stephen era influenced garments in an attempt to reflect Carnaby Street and John Stephen style. Some Mod Clothing gems, a Retro Clothing archive of suitable dandy attire, inspired by 'The King of Carnaby Street' John Stephen.

Let us begin with the Dandy-esque, Edwardian frock coat, the famous 'In Crowd' and 'Rare Breed' Jackets by Madcap England. Two Mod Clothing classics and an Atom Retro staple for quite some years. Avaialble in different fabric variations from the classic cord to a more flamboyant velvet version. Sublime Retro Clothing that is well suited to the John Stephen era of Carnaby Street Mod Clothing.

Another of John Stephen's best sellers was of course the hipster trouser which Atom Retro has in abundance in the form of cool and classic Hipster Flares (in both cord and denim). There's also the odd bootcut flare in stylish Elephant Cord to cast an eye over too! Retro Clothing staples and in tune with the John Stephen Carnaby Boutiques! Atom Retro also offer a more flamboyant range in Hispter flares with their striped 'Holy Roller' Jeans.

Finally, to round things off let's look at something for the ladies. Retro Mod shift Dresses with bold Psychedelic Sixties prints for that ultimate Mod Girl, John Stephen inspired look. Typically audacious attire, the likes of which would not look out of place gracing the window displays in the 'His 'N Hers' or 'Tre Camp' Boutiques.

Bazaar, the first shop opened by Mary Quant in Kings Road, Chelsea,

Mary Quant’s Bazaar: The Woman Who Let the Sixties Loose

If Carnaby Street dressed the boys and Biba wrapped the dreamers in velvet, then Mary Quant outfitted the girls who wanted to run; legs free, spirits high, skirts short.

The woman behind one of the most seismic shifts in British fashion was never meant to play it safe.

Born in Blackheath to Welsh parents, Mary Quant did her schooling, got her Goldsmiths degree, and dutifully began as an apprentice couture milliner. But while she stitched the hats of the well-to-do, she came to a striking realisation: fashion should not be reserved for the moneyed few.

Young Londoners wanted clothes that danced with them, not dictated to them.

Quant sensed a coming cultural quake, youth was ready for fashion that moved as fast as its heartbeat. With her husband/business partner Alexander Plunkett-Greene and lawyer Archie McNair, she braced her knees, grabbed her sewing scissors, and ran straight into it.

A Shop Called Bazaar — and a Revolution Waiting at the Door

1955 was the year everything broke open.

Thanks to Plunkett-Greene’s inheritance, the trio rented space at Markham House, 138A King’s Road, a rather modest spot that would soon become ground zero for the Chelsea Look.

On its first floor, Quant opened Bazaar, pinned with a bold five-petal daisy; a graphic that would soon bloom across Swinging London. They bought small runs of quirky, colourful garments and hoped the fashion gods would be kind.

They weren’t ready for the stampede.

“Sometimes we hardly had enough to dress the window,” Quant later wrote, amazed at just how quickly shelves emptied.

But for all the excitement, Quant wasn’t satisfied. Nothing she could source truly captured the energy she felt pulsing through the streets. So she did what great disruptors do, she made the clothes herself.

The Chelsea Look Takes Shape — One Stitched Hem at a Time

Quant and her first dressmaker sewed through the night, filling Bazaar’s rails with simple shapes built for action, tunics, pinafores, shifts, all immediate, modern, joyful. These weren’t clothes for cocktail parties; they were built for dancing, skipping buses and staying out too late.

Colour mattered. Texture mattered. Pop culture mattered.

And the Mods, their confidence, their music, their rebellion, turbocharged her imagination.

Soon her trademark details emerged:

-

Primary-coloured tights to escape black-and-grey monotony

-

PVC garments that squeaked, shone and shocked

-

Mix-and-match knitwear designed to layer and play

-

And of course skirts that crept higher, week by week

Quant’s store became a style laboratory where young London dressed itself anew every weekend.

The Mini Skirt — and the Moment Fashion’s Rules Snapped

Shorter skirts weren’t a Quant invention; Parisian designers like André Courrèges and John Bates were nibbling hems too. But Quant named it, embraced it, and broadcast it with unbeatable charm.

She always laughed that it wasn’t her idea at all, it was the girls coming into Bazaar tugging hems upward and urging her:

“Shorter! No — shorter!”

Quant obliged. London roared its approval, and suddenly the Mini was everywhere: magazines, malls, buses, catwalks, beaches, dance floors. It wasn’t just a skirt, it was independence in cotton, confidence on legs.

Girls were no longer dressing like their mothers, mothers were trying to keep up with their daughters.

Bazaar Expands — and the Mod Look Goes Global

One shop became two, then three:

-

Knightsbridge in 1961

-

New Bond Street in 1967

Meanwhile, American retailer J.C. Penney spotted Quant’s magic in 1963 and invited her stateside. Vibrant shift dresses, geometric minis and pinafores hit middle America like a stylish meteor. Sales soared, teens rejoiced, and the Mod revolution was officially international.

Her range snowballed:

-

Plastic raincoats

-

Hotpants

-

Patterned tights

-

Knitwear

-

Accessories

Quant became a household name; not just a designer, but a cultural signal flare.

And the honours followed:

-

OBE in 1966 (famously accepted in a Mini skirt)

-

Awards, retrospectives and eventually a permanent place in the fashion canon

Quant herself put it best:

“Snobbery has gone out of fashion… in our shops duchesses jostle with typists to buy the same dress.”

Beyond the Sixties — Colour For Every Corner of Life

As the decade closed, Quant pivoted, not away, but outward.

She created:

-

Cosmetics (as bold as her tights)

-

Beds, linens and household designs

-

Toys, carpets and furnishings

-

And eventually an actual Mini car, painted in Quant motifs

By the 1970s and ’80s, her cosmetics empire eclipsed even her clothing lines.

Eventually, the Mary Quant brand became Japan-led, and Quant stepped aside in 2000 after shaping nearly half a century of design history.

Mary Quant’s Legacy — Fun, Fast and Fearlessly Modern

Quant didn’t just design clothes, she engineered accessibility, joy and empowerment into every hem. She pulled colour into grey streets, gave modernity a wardrobe and told young women everywhere:

Fashion is for you, today, right now, no permission required.

Her daisy wasn’t just a logo, it was a promise:

Youth matters.

Self-expression matters.

And style should never stand still.

Bazaar wasn’t just a boutique.

It was the beginning of fashion’s next chapter and the world is still turning its pages.

As in previous chapters, some select designs from Atom Retro's product portfolio will be on show, to demonstrate a certain amount of Quant flair and to celebrate her lasting impact on fashion. Including Sixties Mod Clothing such as Retro shift dresses, Mini Skirts and colourful knitwear. A collection of Retro Clothing inspired by a legend of British Fashion, Mary Quant.

Lord John: From Petticoat Lane to Carnaby Street

Before the Gold brothers ever dressed Carnaby Street’s hipsters, they were dealing in suede jackets beneath the Sunday sky of Petticoat Lane — one of London’s oldest, loudest, most gloriously unpredictable markets.

Among the fruit sellers, bargain hunters and hustlers calling out their wares, brothers Warren and David Gold learned the first rule of fashion retail:

know what the customer wants before they do.

From that makeshift stall — trading suede to sharp-eyed fashion magpies — they sharpened their eye, honed their instincts, and waited for the right door to open.

That door was on Carnaby Street.

Carnaby Beckons — and a Shop Called Lord John

When Lord John opened at 43 Carnaby Street in 1963, the cultural tremors of the Mod revolution were already shaking the pavement.

But where others saw opportunity, the Gold brothers jumped.

Their boutique arrived in the thick of the John Stephen, led fashion quake, the moment Carnaby Street turned from backwater rag trade alley to epicentre of global cool.

And Lord John took its place in the frontline immediately.

What set Warren and David apart wasn’t just good timing, it was instinct.

With an uncanny knack for sensing what was coming next, the brothers filled their rails with the newest shapes, colours and fabrics the week people wanted them, not six months later.

For the young Mods streaming into Soho, this mattered.

Lord John became less a shop, more a style thermometer, rising with every cultural beat.

In Tune and In Time — Dressing the Stars and the Street

To stay ahead, the Golds didn’t observe the Mod scene, they lived it.

They immersed themselves in the culture, swapped ideas with the bands, watched the cafés and clubs, and made themselves impossible to ignore.

Their reward?

A clientele that read like the NME roll call of Swinging London.

-

The Small Faces kept an account there

-

Members of The Kinks, The Who and The Rolling Stones slipped in for suits and suede

-

Even The Beatles were fans

-

Brian Jones prowled the racks

-

Music writers, models, trendspotters and tourists muscling shoulder-to-shoulder

Inside, it was ** organised chaos** in technicolour.

Lord John overflowed with:

-

Continental tailoring; sharp suits and wet-look raincoats

-

Bright knitwear, including bold ski jumpers

-

Psychedelic shirts and hipsters

-

Suede, cord and denim jackets in every shade

-

And one of the earliest high-street takes on kaftan jackets, straight from counterculture influences

It was affordable, it was modern, it was fast and crucially, it was democratic.

Here, famous musicians queued beside day-trippers and dandies.

Barriers, class, cash, status, dissolved under the beat of the new.

Carnaby Rivalries — and a Name Worth Fighting For

Where there’s success, there’s competition and on Carnaby Street, the battle lines could be sharp.

Lord John’s rise stirred the attention of the street’s reigning monarch, John Stephen and a blistering legal dispute followed when Stephen registered the name “Lord John of Carnaby Street.”

The Golds saw it as poaching.

Stephen insisted he was protecting his reputation, fearing customers thought the shops were linked.

The feud simmered through the mid-sixties, two retail dynasties fighting for the same crown on a street barely wide enough for both.

But rivalry only added to the legend.

People flocked to see what the fuss was about and Lord John’s tills kept ringing.

A Psychedelic Dawn — The Wall That Talked

If Carnaby Street was the epicentre of Swinging London, then in 1967, Lord John became the billboard for its spirit.

The Gold brothers commissioned a massive exterior mural, a three-storey psychedelic fantasia, painted by the young collective Binder, Edwards & Vaughan (BEV).

Swirls, colour, motion; a pop-art hallucination rendered in paint.

It became:

-

A landmark

-

A tourist magnet

-

A fashion press favourite

-

And the backdrop to album covers and film scenes

Carnaby had gone from suede and suits to full Technicolor, and Lord John was leading the parade.

By 1970, the Gold empire stretched to eight boutiques.

In just a few more years, that number hit thirty, as London’s retail revolution spread from Soho to the suburbs and beyond.

After the Sixties — The Gold Name Carries On

The Mod decade ebbed, psychedelia mellowed and Carnaby lost some of its febrile shine but Warren Gold kept innovating.

His Goldrange factory outlet model, tested years earlier in Petticoat Lane, became a blueprint for discount fashion retail, with a flagship “Big Red Building” on Golders Green Road.

Lord John itself passed through corporate hands, absorbed into Raybeck, later rebranded, and eventually folded into Next during the 1980s transformation of the British high street.

But the legacy remained.

Legacy in Thread and Memory

Today, Lord John pieces appear in:

-

The V&A

-

Vintage collections

-

Archive exhibitions

-

Private wardrobes kept like treasure chests

Like many boutiques of the decade, Lord John didn’t just sell clothes, it sold possibility.

It became a crossroads where:

-

Mods and musicians,

-

tourists and tastemakers,

-

teenagers and titans

all fought for the same jacket.

The Gold brothers helped write the rulebook for fast-changing, affordable fashion — decades before the term came into being.

And for a brief, brilliant time, their psychedelic mural was the most photographed wall in London — a monument to a shop that dressed the soundtrack of the Sixties.

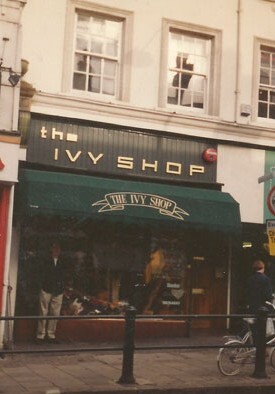

John Simons & The Ivy Shop: Britain’s Passport to the Ivy League Look

Before Mod style exploded into technicolour, Carnaby mayhem and boutique glamour, another fashion story was quietly threading its way into London, clean lines, collegiate cool and American swagger.

At the centre of that movement stood John Simons, and a small shop in Richmond known simply as The Ivy Shop.

Opening in 1964, The Ivy Shop wasn’t loud, flashy or flamboyant and that was its magic.

Where Carnaby Street courted stardom, Simons curated a wardrobe for the thinking man: button-downs, loafers, chinos and jackets inspired by the effortless cool of Cary Grant, Steve McQueen, Paul Newman and the sound of West Coast jazz.

For the young executives, modernists and sharp-minded Mods looking beyond the bright lights of Soho, The Ivy Shop became a pilgrimage.

What Was Ivy? A Quiet Revolution in Style

The Ivy League Look didn’t arrive in Britain through fashion houses or glossy magazines.

It slipped across the Atlantic on the backs of American servicemen; gaberdine trousers, leather brogues and casual shirting worn off duty and swapped through London clubs.

It was:

-

Clean

-

Confident

-

Understated

-

And utterly modern

Button-down shirts with long collars, denim jeans paired with loafers, collegiate ties, soft-shouldered jackets and the now-legendary Playboy creeper soles.

Unlike Mod tailoring, Ivy wasn’t about flash or fuss.

It was minimalism with pedigree, timeless American classics worn with a jazzman’s nonchalance.

As Mods absorbed influences from Italy and the Continent, the Ivy Look created a second stream of inspiration — a fusion of American casual and sharp European tailoring.

At the heart of that fusion stood John Simons.

From Window Displays to Style Legacy — John Simons’ Apprenticeship in Cool

Simons’ fashion education began long before Richmond.

Working as an apprentice window dresser for Cecil Gee, he was at the elbows of the UK’s menswear pioneers. Gee’s shops imported Italian suits and helped shape the wardrobe of London’s jazz underground. Simons learned fast, how clothes sat on the body, how trends evolved, what made a garment desirable.

Then came the real revelation.

Simons secured evening work dressing the window at Austin’s of Shaftesbury Avenue, where jazz saxophonist Lou Austin sold imported American clothing hauled back from trips to New York.

Simons wasn’t there for the paycheck, he was there to study the stock, absorb the cuts, the fabrics, the attitude.

The Ivy Shop was already brewing in his imagination.

Richmond’s Ivy Temple — A Mod Alternative

When The Ivy Shop finally opened its doors, it instantly became:

-

A hub of coffee bar culture

-

A destination for jazz devotees

-

A beacon for Mods who craved subtler style

-

And a shrine to American authenticity

No psychedelic prints.

No military parkas.

No glittering Chelsea boots.

Instead, racks carried:

-

Prince of Wales check suits

-

Dogtooth trousers

-

Oxford button-down shirts

-

Basketweave and brogue shoes

-

College ties

-

Crombie coats

-

Classic three-button jackets and mohair suits

Suedeheads and later skinheads with a taste for sartorial neatness, became devoted customers.

Bands and stylists used Ivy attire in photo shoots.

And people travelled from across Britain just to get their hands on imported American stock.

In a decade known for flamboyance, The Ivy Shop proved that quiet style could speak the loudest.

Beyond Richmond — Squire, Covent Garden & a Lasting Legacy

Demand grew, and with it Simons’ empire.

His second shop, Squire, opened on Brewer Street, reinforcing his reputation as the importer of authentic US clothing.

Then came the legendary J. Simons Shop, opening in Covent Garden in 1981, keeping the Ivy flame burning well beyond the Sixties.

Simons stocked Baracuta, Levi’s, Bass Weejuns, McGregor, Arrow and other heritage staples, alongside carefully curated vintage, a forward-thinking move as clothing prices soared.

It was here that Simons left one of his greatest cultural footprints, christening the Harrington jacket, after Peyton Place character Rodney Harrington.

The name stuck, the jacket became iconic, and a piece of Americana gained a very British identity.

The Ivy Shop’s Place in Fashion History

The Ivy Shop wasn’t just another boutique; it was a doorway to a different aesthetic, one rooted in heritage but worn with modern swagger.

Where Mary Quant reshaped womenswear and Lord John fuelled Mod flamboyance, John Simons gave British menswear something equally revolutionary, relaxed elegance with substance.

It taught a generation that:

-

casual could still be classy,

-

subtle could be stylish,

-

and the sharpest look of all might just be the simplest.

Decades on, the Ivy Look continues to cycle back into fashion and every revival carries John Simons’ fingerprint.

I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet: When Victoriana Met the Mods

Before kaftans swept Carnaby and paisley turned psychedelic, nostalgia, crisp, playful and proudly eccentric, quietly marched into the Swinging Sixties.

At its head stood a boutique with a name impossible to forget:

I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet

Founded by Ian Fisk, John Paul and Robert Orbach, the shop opened a door to an entirely new aesthetic.

This wasn’t continental tailoring or Ivy League casual.

It was Victoriana, military grandeur, and retro rebellion, a sartorial wink to Britain’s past, pressed into service for its style-conscious present.

In a decade defined by reinvention, Lord Kitchener’s Valet proved that old could be new and that the British Empire’s cast-offs could become the hottest uniform in youth culture.

Before the Valet — A Gap Waiting to Be Filled

By the early 1960s, London had boutiques for Mods, dandies, and rockers but nowhere for those wanting something rarer, stranger, or steeped in story.

Military tunics, Guardsman jackets, Victorian frock coats, medals, epaulettes, crested buttons…

These treasures existed only in dusty army surplus bins and antique auctions, far from the hands of the fashion-forward.

Lord Kitchener’s Valet changed that overnight.

Fusing:

-

Retro clothing

-

Vintage furnishings

-

Military regalia

-

Curios and objets d’art

the founders tapped into a rising fascination with heritage, theatricality and identity. Their shop became a stage where shoppers could literally wear history.

A Name Fit for a Legend

The name, long, eccentric, and proudly British, was pure inspiration.

Ian Fisk chose I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet because it conjured Victorian pageantry and instantly announced what the shop stood for:

anachronism with flair.

In a landscape of boutiques called Bazaar, Lord John and Hung On You, this name stopped people in their tracks.

It promised mystery, mischief and transformation and it delivered.

The Day Everything Changed — Lennon, Jagger & a Tunic

Business was steady. Interest simmered. And then lightning struck.

One morning in 1966, as Robert Orbach recalled, three unlikely customers walked through the door:

-

John Lennon

-

Cynthia Lennon

-

And Mick Jagger

Jagger walked out with a red Grenadier Guards drummer’s jacket, bought for mere pounds from former Moss Bros and surplus stock.

That evening he wore it on Ready, Steady, Go! performing Paint It Black.

By sunrise, London had changed.

Crowds, hundreds deep, queued outside.

The entire shop was cleared by lunchtime.

Suddenly, military tunics were the uniform of the revolution.

From that moment, the Valet became outfitter to the stars:

-

Eric Clapton bought a tunic as Cream took off

-

Jimi Hendrix immortalised his in iconic photographs

-

Pop musicians, aristocrats, art students and office clerks all wanted in

The boutique didn’t chase fashion, it created it.

Rebellion, Respectability — or Simply Style?

Not everyone was amused.

Some former soldiers bristled at the sight of Guards jackets repurposed for nightlife.

Others saw the look as anti-establishment; a youth movement wearing literal rebellion on their sleeves.

But most recognised it for what it was:

-

playful,

-

flamboyant,

-

and undeniably modern.

In a decade when traditions tumbled, appropriating the past became its own form of cool.

March of the Valets — From Portobello to the King’s Road

The first shop opened in Notting Hill’s Portobello Road in 1964, and success quickly demanded expansion.

Soon there were branches in:

-

Wardour Street

-

Fouberts Place

-

Piccadilly Circus

-

Carnaby Street

-

And the King’s Road

The Carnaby shop, leased from Lord John’s Warren Gold, became prime territory, footsteps away from the Marquee Club, ensuring every band in London eventually passed by.

By 1966, the boutique had earned such cultural capital that The New Vaudeville Band released a single titled “I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet.”

Even Sgt Pepper owes it a salute; Peter Blake credited the shop’s displays as inspiration for the Beatles’ psychedelic military costumes on their landmark album cover.

Few boutiques in fashion history can claim such impact.

Laying Out the Last Outfit

Lord Kitchener’s Valet carried its quirky standard through the Sixties and into the Seventies, finally closing in 1977.

But its legacy marches on.

It proved that:

-

fashion could mine history without being stuck in it

-

vintage could be modern long before the word existed

-

and clothing could communicate personality, irony and fantasy all at once

From the Stones to the streets, from Portobello Road to pop-art album covers, I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet didn’t just sell jackets —

it rewrote the rules of how young Britain dressed, imagined itself, and reclaimed its past.

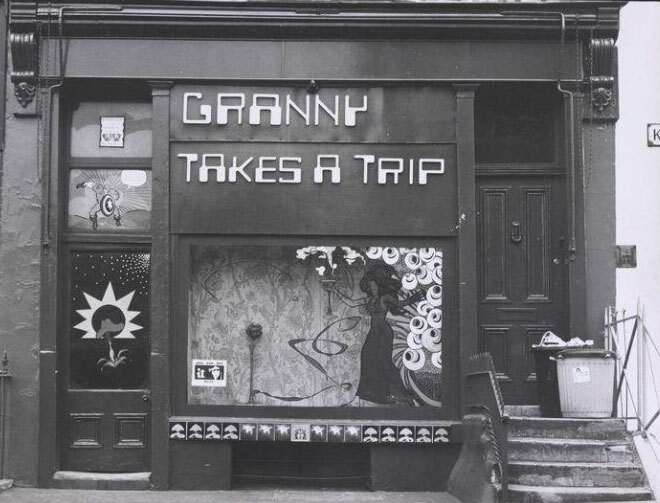

Granny Takes a Trip: Psychedelia at the World’s End

Turn on, tune in, drop out and step into a shop like no other.

Granny Takes a Trip wasn’t merely a boutique. It was a signpost for the culture-shifting rumble of the late 1960s, a moment when fashion, music, art and attitude collided in an explosion of colour, counterculture and unbridled imagination. As London’s underground scene began to crackle with psychedelic energy, the city’s boldest shopkeepers sensed something electrifying in the air. Among them stood Sheila Cohen, Nigel Waymouth, and the Savile Row–trained tailor John Pearse, the trio who took a once-unfashionable corner of the King’s Road and turned it into a global style beacon.

The World’s End Awakens

When Granny Takes a Trip opened in 1966 at 448 Kings Road, Worlds End was hardly the epicentre of anything. But inside those doors, Victorian velvet met electric colour, Edwardian tailoring mingled with Hendrix riffs, and kaleidoscopic chaos was somehow stitched into impeccable jackets. Vintage clothing was elevated from dusty relic to radical icon, a fresh rebellion powered not by scruffiness, but by cut, craft and sheer audacity.

The name itself was the manifesto:

Granny — the past, tradition, Victoriana

Takes a Trip — the future, psychedelia, perception flipped

Together they summed up the decade’s most daring fashion philosophy: only by reshaping the past could you dress for tomorrow.

A Boutique Built Like a Dream

Inside, shoppers stepped into what Nigel Waymouth called a New Orleans bordello by way of Art Nouveau hallucination. Purple haze paintwork, perfumed incense, marbled walls and enlarged Aubrey Beardsley illustrations set the scene. At the back, a glowing Wurlitzer hummed its invitation. This wasn’t shopping, it was immersion, altered consciousness without a single tab of acid required.

Cohen and Waymouth sourced antique garments and vintage Victoriana, while Pearse expertly remodelled them, creating the longline jackets, paisley shirts and Liberty-print finery that became the boutique’s signature. Quality ruled. Even in the haze, Granny’s needlework was sharp.

A Shop Front That Stopped Traffic

Psychedelia didn’t end at the door, it spilled across the street. Granny Takes a Trip became legendary not only for its wares, but for its ever-changing, always-breathtaking façade. When the window smashed, Waymouth, now half of the psychedelic art duo Hapshash and the Coloured Coat — simply turned mishap into masterpiece.

Native American chiefs Low Dog and Kicking Bear beamed down in brilliant gradients;

Jean Harlow shimmered across the frontage like a movie dream;

A 1947 Dodge car smashed through the wall, or seemed to.

Here was theatre as advertising. Art as invitation. Everyday Londoners, whether ready or not, were confronted by the colour and chaos of a cultural revolution.

Famous Followers and Heavy Influences

Like Lord Kitchener’s Valet, Granny Takes a Trip caught lightning when rock royalty discovered it.

The Beatles wore its garments on and off record sleeves.

Jagger, Pallenberg, The Animals, The Pretty Things, Hendrix’s bandmates, and the Mods turned Freaks and Flower Children all claimed their piece.

Granny’s inspired songs, magazine spreads, international press and an entire era’s aesthetic. The shop didn’t just follow fashion it defined it.

New Owners, New Eras, New Visions

By decade’s end, Cohen, Waymouth and Pearse were ready to evolve elsewhere. In 1969, Freddie Hornick acquired the store and radicalised it again — ushering in flamboyant tailoring, appliquéd velvet, stacked heels and glam rock swagger. Bowie rotated through. Marc Bolan shimmered in Granny suits. Gene Krell and Marty Breslau helped export the name to New York and L.A., where the legend continued into the late 1970s.

The Legacy

Though the Kings Road shop finally closed in 1974, Granny Takes a Trip remains a benchmark, not just for psychedelic fashion, but for what a boutique could be.

A place of invention, not imitation.

A laboratory of style.

A portal to another mind.

Granny didn’t just take a trip, she led one, and fashion followed.

⭐The Pretty Things: Mod Clothing in the Swinging Sixties.

If style was the soul of Mod, then clothing was its unmistakable language, spoken boldly, tailored sharply, and worn with total conviction. As the movement gathered pace, wardrobes became curated expressions of identity, aspiration and belonging.

What Mods chose to wear wasn’t mere fashion, it was a declaration of taste, modernity and social standing. Every garment held meaning, from the razor-cut suits of weekday city streets to the riot of colour and continental cool unveiled each weekend.

With influences drawn from jazz clubs, Vespa scooters, European cafés and Swinging London’s tailors, Mod style moved quickly, redefining what young Britain looked like. These were the pieces that formed the uniform; sleek, sharp and unapologetically stylish.

Drainpipe Jeans — When the Line Got Sharp

Before Mods were decked head-to-toe in sleek tailoring, it was the trouser leg that drew the first line in the sand. Drainpipe jeans, thin as the name suggests and hugging the leg right down to the ankle, marked a decisive break from post-war normality. Emerging in the late fifties, these tightly cut trousers were a daring uniform for the young and the restless. Parents frowned, teachers raged, and older generations muttered about impropriety, yet the very controversy helped cement their cool.

Unable to buy the real thing, inventive teens resorted to clandestine alterations, tapering wide legs into narrow shafts with hidden stitches and a smuggled sewing machine. By the dawn of the sixties, the look had spread: the uniform of coffee bar bohemians, jazz club regulars and early Mod pioneers. Today, drainpipes remain a cornerstone of Mod styling; unisex, lean, austere, and effortlessly sharp, the blueprint for every “skinny” jean that came after.

The Mod Suit — A New Uniform for a New Generation

If the scooter was the chariot of the Mods, the suit was their armour. The Mod Suit was something entirely new; clean, modern, continental and unapologetically youthful. In East London around 1958, sharp-eyed young men began discarding the flamboyant drape jackets of the Teddy Boys for something cooler and more streamlined: the Italian-inspired silhouette.

This wasn’t stuffy British suiting for bowler-hatted clerks; it was rakish art in motion. Narrow lapels, a shorter jacket length, slim fitted trousers (sometimes cropped), lightweight fabrics and minimal fuss. French New Wave cinema, Fellini films and Italian tailoring houses all played their part. Add a crisp button-down shirt, knitted tie or silk accessory, and a Mod instantly stood out from the crowd; sleek, smart and utterly modern.

Tailoring wasn’t a luxury, it was a necessity. Suits were saved for, customised and obsessively cared for. The cut had to be perfect; the fit exacting. Mods measured themselves against Carnaby Street mannequins or Savile Row influence, then pushed tailoring into new territory. For weekday city streets, the suit whispered sophistication; for weekend clubs and all-night dancing, it sparkled with swagger. In every stitch lay a statement: we choose how we dress, and we dress for the future.

No Mod wardrobe was complete without it. Suited and booted wasn’t just a saying, it was a creed.

The Button-Down Shirt — Cool, Clean and Perfectly Pinned

Among the many garments that came to define the Mod wardrobe, none captured the crisp, modern edge of the movement more completely than the button-down shirt. Smart yet relaxed, stylish yet understated, it was the bridge between weekday polish and weekend play, the perfect expression of Mod control and confidence.

Inspired heavily by American Ivy League style, the button-down shirt crossed the Atlantic in the late 1950s, carried by jazz-loving servicemen, enterprising importers and those who tracked down the latest looks in obscure London menswear shops. While Britain’s traditional shirts sported wide collars prone to flapping open, this new style offered something radically different, points neatly secured with small buttons, creating a clean, pin-sharp look that complemented the slim Mod silhouette.

Once Mods discovered the button-down, it became a quiet obsession. Shirts were chosen carefully: perfect collars, just the right length, and always crafted from quality fabrics. Oxford cloth for everyday wear, slim poplin or fine cotton for club nights, and occasionally a dash of check or stripe for extra flair. Colours tended toward ice-cool tones; French blue, bright white, pale lemon, worn beneath a narrow-lapelled suit by night or paired with drainpipes and a lightweight windcheater by day.

The button-down also aligned seamlessly with Mod values: minimal, modern and precise. It was tailored enough to look sharp, casual enough for a scooter ride, and versatile enough to take its wearer from café to club without missing a beat. For many Mods, the collar itself became a badge of style, fastened up for a clean, composed appearance or buttoned down fully in a manner copied from jazz musicians and Ivy League athletes.

As the sixties rolled on, the button-down became ubiquitous. From Soho tailors to Carnaby Street boutiques, from The Ivy Shop to bespoke Mod outfitters, the shirt cemented itself as part of both the everyday and the iconic. It appeared in album photos, film stills, and on the backs of everyone from sharp-dressing city clerks to scooter-riding teenagers burning through the night.

Today, Mods, original and revival, still prize the button-down as a cornerstone of their wardrobe. Its simplicity remains its power: a clean line, a perfect collar, and a subtle nod to the American modernism that helped shape a British subculture. Worn with pride, precision and purpose, it is, and always will be, a Mod essential.

Winklepicker Shoes & Chelsea Boots — Sharp From the Ground Up

A Mod may start with the suit, but the outfit was judged from the shoes up. The Winklepicker; sleek, elongated, and ending in a wicked point, was the first footwear phenomenon to complement Mod tailoring. Inspired by rock ’n’ roll, coffee-bar culture and rebellious flair, the sharp toe became a badge of honour. The more exaggerated the point, the more daring the wearer. By the early sixties, the style came in polished leathers, suede finishes and even decorative buckles, perfect partners to the clean lines of Mod dress.

As the decade moved on, the Chelsea boot stepped into the spotlight. Originally designed for horsemen, the ankle-hugging elastic-sided boot was refined for the dance floor. Slim, minimalistic and versatile, the Chelsea boot embodied Mod functionality and fashion in equal measure. Soon, the addition of the Cuban heel, steep, stylish and slightly theatrical — lifted the boot into iconography. The Beatles sealed its reputation, and from then on the Chelsea was a must-have: black leather for urban cool, black suede for late-night swagger.

Together, Winklepickers and Chelsea boots gave Mods the final piece of the puzzle: elegance, attitude and a step ahead of the establishment. They were the finishing touch to the Mod mantra; stylish, sharp and always moving forward.

The Harrington Jacket — Lightweight Legend of the Mod Wardrobe

When Mods weren’t suited and booted, they turned to one jacket above all others: the Harrington. Lightweight, windproof, shower-resistant and effortlessly stylish, it became a defining symbol of British street style, a garment that bridged Ivy League simplicity, rock’n’roll swagger and scooter practicality.

Baracuta: The Birth of an Icon

The original Harrington Jacket began life long before the sixties. It was created in 1937 in Stockport, Cheshire, by the Miller brothers, John and Isaac, founders of the Baracuta Company. Their mission was simple but ambitious: to design a short jacket that was weatherproof, comfortable and smart enough to be worn casually or with tailoring. The result was the Baracuta G9, a blouson‐style jacket with a zip front, elasticated waistband and cuffs, and a neat buttoned collar.

One detail made the jacket instantly distinctive: its lining. In 1938 Baracuta was granted permission to use the Fraser Clan tartan in its interior; a flash of aristocratic colour hidden beneath a clean, modern exterior. From that moment, the true Harrington silhouette began to take shape: trim, tidy and unmistakably British.

From Peyton Place to the Pavement

Though loved by golfers and adopted by GIs, it was the sixties Mod scene that gave the jacket a second life. The fit, streamlined, short and fuss-free, worked perfectly over pressed trousers and button-down shirts. It didn’t get tangled on scooters, was smart enough for early evening cafés, and resilient enough for late-night rides.

Its name, though, came almost by accident. Rodney Harrington, a character played by Ryan O’Neal in the American TV serial Peyton Place, wore a Baracuta G9 so regularly that young Mods began asking for “a Harrington jacket”. John Simons of the Ivy Shop adopted the phrase and fashion history was sealed.

Soon, everyone wanted one: Steve McQueen wore it with understated confidence in The Thomas Crown Affair, Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra sported theirs off-stage, and later artists from Paul Weller and The Clash to Liam Gallagher and Daniel Craig kept the legend alive.

G9, G10, G4 — Evolution of a Classic

Baracuta’s jackets evolved into a now-famous trio:

-

G9 — the original Harrington, with the iconic umbrella-shaped five-point back vent

-

G10 — similar shape, but without the vent

-

G4 — a waist-adjustable, open-hem version

Regardless of variant, the elements remain the same: simplicity, versatility and quiet confidence.

The Harrington Through the Ages

Like the Mod movement itself, the Harrington never stood still.

-

1960s — Ivy‐League Mods and clubland cool

-

1970s–80s — adopted by Skinheads, Scooterists and the Two-Tone crowd

-

1990s Britpop — indie kids rediscovered it, Noel Gallagher leading the charge

-

2000s onwards — a global wardrobe essential

Baracuta is still revered, the connoisseur’s choice but a wealth of British brands now produce their own takes. Merc London’s bold palettes, Ben Sherman’s clean lines and checked linings, and countless heritage labels keep the silhouette alive.

Today, the Harrington remains the casual jacket of choice for Mods, revivalists and style purists alike. Pair it with a button-down, drainpipes and suede shoes and the Mod look is instantly complete.

The Parka — The Armour of the Scooter Generation

If the Harrington was the Mod’s cool, casual jacket, the Parka was their shield; a cocoon against the cold, the wind and the grime of the London streets. Oversized, functional and instantly recognisable, it became more than clothing: it became the unofficial uniform of a movement.

Humble Beginnings: From Eskimo Roots to Army Surplus

The Parka’s lineage predates fashion entirely. Mod Parkas descend from garments used by Inuit and Yup’ik peoples; ingenious hooded coats built for survival in Arctic climates. The U.S. military adapted these designs for aviation and infantry in frigid theatres of war, producing the now-legendary M-51 and M-65 fishtail Parkas.

After WWII, mountains of surplus army gear were sold cheaply, and Mods, always on the hunt for value and distinction, spotted their opportunity.

Practical Style for a Style-Obsessed Movement

Mod clothing tended toward the trim, tailored and immaculate which made scooter riding risky business. Suits and polished shoes were no match for British drizzle, splattered roads and exhaust fumes.

Cue the Parka:

-

Warm and windproof

-

Long and protective — perfect coverage over a tailored suit

-

Hooded and fur-trimmed — essential for winter scooter runs

-

Cheap — army surplus instead of Savile Row

Soon, no serious scooter rider would be seen without one.

The Fishtail and the Flair

While surplus Parkas were originally drab army green, Mods quickly made them their own. They:

-

customised them with patches, badges and union jacks

-

soaked them in scooter oil and cigarette smoke

-

dyed them to match Vespa and Lambretta colour schemes

-

removed or altered linings for summer jaunts

The fishtail back, designed to cover a soldier’s legs or tie around the thighs, became a Mod hallmark, fluttering behind scooters like regimental banners.

Cinema Immortalises a Coat

By the time Quadrophenia hit cinemas in 1979, the Parka had moved beyond practical wear into cultural mythology. Phil Daniels’ Jimmy astride his Lambretta, covered in mirrors and wrapped in a full-length Parka, became one of the most enduring images of British youth culture. The album art alone cemented the coat’s place in Mod lore.

From that moment, Parkas were not just useful, they were Mod.

From Surplus to Catwalk

Though the original always holds the most romance, the Parka eventually shifted from surplus bins to fashion stockrooms:

-

Designers reimagined it in poplin, gabardine and even leather

-

Colours moved beyond khaki to navy, black, mustard and tartan‐lined variants

-

It became a must-have for both Mods and the burgeoning skinhead and scooter scenes

-

By the 1990s Britpop wave, Oasis fans were wearing them as clubwear, not rainwear

A coat born for war became a garment born for youth, tribe and identity.

Together

Where the Harrington is sharp, neat and urban, the Parka is rugged, protective and communal.

One for café culture, dance floors and dates.

The other for seaside rides, wet pavements and late-night journeys home.

Two sides of the same movement and indispensable pillars of Mod style.

The Peacoat - From the High Seas to High Style

If the Harrington is the Mod’s casual classic and the Parka its scooter armour, then the Peacoat sits proudly as the sharp, winter-ready option, a stylish symbol of naval history, Ivy influence and Mod cool.

The Peacoat is one of the oldest garments to make its way into the Mod wardrobe. Its origins lie in 18th and 19th century European navies, most notably the British Royal Navy, where ratings wore a short, double-breasted coat cut from thick, heavy wool.

Designed to withstand cold salt air and brutal winds at sea, the coat featured:

-

A broad, wide lapel that could be buttoned up to the chin,

-

Double-breasted closure for warmth,

-

Large anchor-engraved buttons for grip with gloved hands,

-

Slash hand-warmer pockets,

-

And the iconic melton wool, tightly woven to shrug off rain.

Dutch sailors referred to it as the "pijjekker" or "pije" coat, after the coarse wool it was constructed from, a name which, with a little Anglicisation, becomes “Peacoat”.

Mods Make It Their Own

By the late 1950s and early ’60s, the Ivy League look had captured the imagination of sharp-dressing young British Mods. The Peacoat, neat, tailored, and a perfect contrast to the longer, looser Parka, slid naturally into the Mod wardrobe.

For Mods, the Peacoat offered:

-

Smartness without formality — ideal for pubs, clubs and coffee bars,

-

A polished silhouette that suited tailored trousers and polished shoes,

-

Warmth on a scooter without the bulk of military surplus.

It soon became a uniform for stylish winter nights worn with a slim knitted roll neck or crisp button-down shirt, drainpipe trousers and Chelsea boots.

Melton Wool & Masculine Elegance

Part of the jacket’s enduring appeal is its shape:

Structured but not stiff, military but not aggressive, smart but still youthful.

Classic features include:

-

Navy blue or black melton wool

-

Double-breasted front

-

Large buttons (often still marked with anchors in tribute to its roots)

-

Vertical or slanted front pockets

-

Mid-hip length, giving a sleek line over narrow trousers

The silhouette is flattering on men and women alike, another reason it became a unisex Mod favourite.

Beyond Mod: Cinema, Rock & Pop

Like the Harrington, the Peacoat owes some of its mythology to the silver screen.

It has appeared on:

-

James Dean and Paul Newman,

-

Jack Kerouac-inspired Beat writers,

-

Bob Dylan on early album covers,

-

Robert Redford, Woody Allen, and Jude Law.

Every few years, the Peacoat resurfaces atop the style ladder yet the design hardly changes, proof of its perfect form and timeless function.

Modern Interpretations

Most Mod clothing brands continue to pay homage to the classic Peacoat:

-

Baracuta, Gloverall, Schott and Crombie produce heritage versions,

-

Indie-Mod labels offer slimmer cuts,

-

And contemporary designers experiment with colours, fabrics and elongated lengths.

But whether contemporary or strictly traditional, the Peacoat’s essence remains the same; naval roots, Mod refinement and enduring cool.

A Winter Icon

The Peacoat is the Mod coat that bridges the gap between casual and tailored, the clean-lined answer to biting winter air, ideally worn with a confident stride and a well-tuned scooter rumbling nearby.

A style staple then and still one today proving that the best designs never date.

⭐Swinging Style: An Introduction to Mod Womenswear

Mod womenswear didn’t just follow fashion it changed it.

As the 1960s unfolded, a powerful new youth-driven movement swept Britain, sparked by music, clubs, scooters and a desire to break free from the conventions of their parents’ world. Young women were at the heart of this revolution, and their clothes became a bold visual language of freedom, individuality and modern living.

Unlike the hourglass silhouettes of the 1950s, Mod style was forward-facing, clean-lined and pared back. Inspired by European tailoring, art-school cool, and the rise of design-led boutiques, young women embraced a brand-new aesthetic. Hems climbed above the knee, shapes shifted into sharp A-lines, and clothes were no longer designed simply to flatter but to excite, express and empower.

This was the birth of:

-

The mini skirt — a daring declaration of independence

-

The shift dress — simplicity reimagined as style

-

Go-go boots — footwear built to be seen

-

Graphic monochrome, bold brights and Pop Art patterns

-

Androgynous tailoring, borrowed — and improved — from the boys

Crucially, Mod womenswear celebrated movement and modernity. Clothes were made to dance in at cellar clubs, ride pillion on a scooter, or prowl London pavements in search of the next boutique.

From Mary Quant’s playful revolution on the King’s Road, to Jean Shrimpton’s streamlined elegance, Twiggy’s boyish glamour and the polished Italian-inspired styles of Soho’s sharpest girls, Mod women shaped a whole new fashion landscape.

Their look was not about status or age it was about attitude.

Mod womenswear remains an enduring touchstone because it rewrote the rules, embracing:

-

Youth over tradition

-

Design over decoration

-

Confidence over conformity

This was the wardrobe of a generation determined to dress for the world they were building, not the one they inherited.

The Mini Skirt — A Hemline that Changed the World

Few garments define the spirit of the 1960s quite like the mini skirt. More than a fashion trend, it became a cultural landmark, a symbol of youth, liberation and the new social freedoms sweeping Britain.

While hemlines had been rising slowly since the 1950s, it was Mary Quant; the boundary-pushing designer of Bazaar on the King’s Road, who took the decisive leap above the knee. Quant didn’t invent the mini skirt in isolation, but she championed it, popularised it and personified its cheeky new attitude. With her cropped haircut, playful wit and instinctive feel for what young women wanted, she turned the mini from a daring experiment into an international revolution.

The mini skirt’s power lay not only in its look but in what it represented. For the first time, women, particularly teenagers and young adults, were dressing for themselves rather than for convention. Minis allowed for movement, dancing, walking, running for the bus, and fitted perfectly into a lifestyle built around clubs, cafés and scooters. Bright colours, bold geometric prints and simple lines accentuated the look, giving the mini an unmistakably modern edge.

By the mid-1960s the mini had become the defining silhouette of the decade. London boutiques led the way, with Quant joined by designers like Foale & Tuffin, Barbara Hulanicki of Biba and many more. The press dubbed London “the fashion capital of the world,” and Mod girls proudly put the city’s style on global display.

From Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton to student fashionistas on Carnaby Street, the mini skirt embodied independence, youth culture and a refusal to look back. Its legacy has endured, reappearing every decade since and it remains permanently linked to the rebellious, joyful modernism of the Mod era.

The Shift Dress — Clean Lines, Bold Shapes, Pure Mod

If the mini skirt captured the daring spirit of the 1960s, the shift dress embodied its streamlined aesthetic. Sleek, simple and effortlessly stylish, the shift was the dress of choice for Mod girls, a garment that perfectly echoed the movement’s love of modernity, geometry and freedom.

Cut straight through the body with little shaping at the waist, the shift dress defied the traditional hourglass silhouette of the 1950s. Gone were corsets, layers and frills, replaced with a silhouette that celebrated youth, ease and movement. In the shift dress, women were free not only to look modern but to live modern.

Mod designers seized on this shape and reinvented it in countless ways. Mary Quant’s versions were playful and sporty, often in bold colours and crisp fabrics. Foale & Tuffin brought imaginative prints and edgy tailoring, while boutique labels on Carnaby Street offered dazzling variations; from stark monochrome to Pop Art brights, op art patterns and futuristic metallics.

The shift dress also suited every environment in Mod life:

-

By day: paired with flats or low heels for school, work or boutique browsing

-

By night: worn with mini length boots or court shoes for clubs, gigs and dancing

-

On scooters: sleek enough to sit comfortably beneath a parka

Design simplicity made it the perfect canvas for experimentation. Contrasting pockets, decorative buttons, Peter Pan collars, panel details and colour blocking became iconic stylistic signatures of the Mod scene. The result was clothing that looked sharp, modern and unmistakably forward-thinking.

Worn by icons such as Twiggy, Cathy McGowan and Marianne Faithfull and countless girls who filled London streets with colour, the shift dress remains one of the most instantly recognisable shapes of the decade. It perfectly expressed what the Mod movement stood for: clean design, youth culture, and a refusal to be bound by the past.

Patterned Tights — Legs Made for Swinging

If the mini skirt was the icon of 1960s womenswear, the patterned tight was its perfect partner in crime. As hemlines rose higher than ever before, bare legs demanded a fashionable new frame and tights stepped boldly into the limelight.

Before the early sixties, most women wore stockings held up by suspenders; restrictive, fussy and utterly incompatible with dancing the night away in a Mary Quant mini. The arrival of nylon tights was nothing short of revolutionary. Suddenly, legs could be completely covered, comfortably, and with a smooth, clean finish ideal for the new Mod silhouette.

A Canvas for Colour and Pattern

As fashion became more daring, tights evolved from a practical necessity into a playground for self-expression. Solid black and flesh tones quickly gave way to:

-

Bright primary colours

-

Opaque jewel tones

-

Psychedelic swirls

-

Graphic op art geometrics

-

Florals, fishnets and stripes

Mod girls embraced anything that made their outfits bolder, brighter and more striking. Patterned tights transformed legs into living modern art — another opportunity to showcase individuality.

Pamela Mann — The Name Behind the Look

At the forefront of this hosiery revolution stood Pamela Mann, a label synonymous with creativity, colour and statement-making legs. Founded in the 1960s, the brand quickly became one of the most prominent suppliers of patterned and coloured tights to boutiques and fashion lovers alike.

Pamela Mann pieces captured exactly what Mod girls wanted:

-

Affordable but stylish legwear

-

Patterns that mirrored the art and music scenes

-

A dash of rebellion wrapped in nylon and lycra

Whether spotted on the King’s Road, Carnaby Street or tearing up the dancefloor at The Marquee, Pamela Mann tights helped define the playful, youthful energy of the era.

Legs for the Limelight